2024 One For the Heroes, Central Nebraska Today

LEXINGTON — A Lexington-Cozad resident participated in three campaigns in the South Pacific during World War II and was wounded during the New Georgia campaign.

Thomas, “Tom” Kugler was born on June 19, 1908, in Cozad, the son of Charlie Kugler. Before the war he was a tractor operator and helped out on the family farm. The family later moved to Lexington.

Kugler was inducted into the United States Army on May 1, 1942, at Fort Crook, Nebraska. According to a newspaper clipping provided by the Dawson County Historical Museum, Kugler trained at Camp Bowie, Texas, Camp Shelby, Miss., and Lessville, La.

He would later join the 172nd Infantry Regiment, of the 43rd Division.

A world away, the Empire of Japan had been on a war of conquest after the attack on Pearl Harbor. The Japanese had seized islands throughout the South Pacific in an effort to take their resources for their empire.

Their defense plan hinged upon fighting fanatically for islands people in the United States had never heard of and hoping Americans would quickly tire of the high casualties.

After the Battle of Midway, the initiative swung in favor of the United States, which began a plan to dislodge the Japanese from their island footholds. By 1943 the protracted battle of Guadalcanal had ended with the American’s forcing the Japanese off the island.

Unite States Army General Douglas MacArthur, wishing to return to the Philippines had devised a plan to move through the South Pacific islands and neutralizing the strategically important Japanese base in Rabaul. The plan would later become known as Operation Cartwheel.

One area which needed to be taken was the New Georgia islands in the central Solomon Islands. The Japanese had prepared against Allied landings and by June 1943, there were 10,500 and 9,000 on a neighboring island. They were well dug into the jungle terrain and prepared.

Kugler and the entire 1st Battalion of the 172 Infantry Regiment landed on the island on July 2 and 3 and began to move to the New Georgia mainland as part of an effort to secure Muda Point. The Japanese had built an airfield on the point, and it was strategically important to the Americans.

By July 6, the concentration of American forces was complete and began to advance toward the Barike River which was about three miles away, on their way to Munda Point. The effort would be beset by issues, and this would lead to a slow grinding assault with high casualties.

Prior to the start of the campaign Allied intelligence had assessed there were between 2,000 and 3,000 Japanese personnel in the Munda area, in reality there were 4,500 men.

Planners also failed to appreciate that the land between the beaches and Munda was not conducive to a quick approach, troops had to transverse a single, narrow track through dense jungle, which was crossed by flowing creeks and streams and flanked by rocky ridges and deep ravines.

Kugler and the advancing troops found navigation difficult and were forced into a narrow front as the Japanese resistance stiffened.

In an effort to break through the Japanese lines, the 172nd was ordered to carry out a flanking maneuver and attack the Japanese positions in the rear on July 9. Their sister unit, the 169th, was to continue the frontal assault.

The Japanese commander had correctly deduced the Americans intent and moved troops to counter the 172nd flanking maneuver. Kugler would have been involved in the fighting as the unit gained only 1,100 yards. The 169th, held up by Japanese snipers hidden in the trees with flashless rifles, was unable to gain any ground at all.

By July 11, the 172nd and Kugler was ordered south, while the 169th continued up the Munda trail. During the evening, the naval task force in the area attempted to help troops with a 40 minute bombardment, but it did little. Shells fell a full mile ahead of U.S. troops due to safety reasons.

The following day, the 172nd and Kugler were unable to make much progress. The situation was made worse when the Japanese were able to land reinforcements from 16 barges. The next day would be a hard day for the 169th.

On July 13, a Japanese battalion discovered a gap in the line between the 169th and the 172nd and cut off the Americans on the high ground. The 169th were subjected to repeated counterattacks from the Japanese and the unit suffered over one hundred killed and wounded on the first day alone.

The Japanese infiltration tactics at night met with success and unnerved the Americans. An official report from the 169th noted, “when the Japanese made their presence known . . . or when the Americans thought there were Japanese within their bivouacs, there was a great deal of confusion, shooting, and stabbing.”

The report continued, “Some men knifed each other. Men threw grenades blindly in the dark. Some of the grenades hit trees, bounced back, and exploded among the Americans. Some soldiers fired round after round to little avail. In the morning no trace remained of the Japanese dead or wounded. But there were American casualties; some had been stabbed to death, some wounded by knives. Many suffered grenade wounds, and 50 percent of these were caused by fragments from American grenades.”

The 172nd was able to finally dislodge themselves and reached their objective on July 13. Their progress was made difficult as they had to push through a swamp and came under Japanese mortar fire. By this point in the day Kulger and his unit were running short on water and supplies.

The situation was improved when a second landing was carried out near the position of the 172nd which brought supplies and reinforcements from the 103rd Infantry Regiment, which linked up with Kugler’s unit.

By this point Kugler and the 172nd were on the edge of the heavier Japanese defensive positions and the airfield at Munda Point was still out of reach. The conditions were beginning to wear on the Americans, as many troops were suffering from dysentery and combat stress was made manifest as fire discipline began to decline.

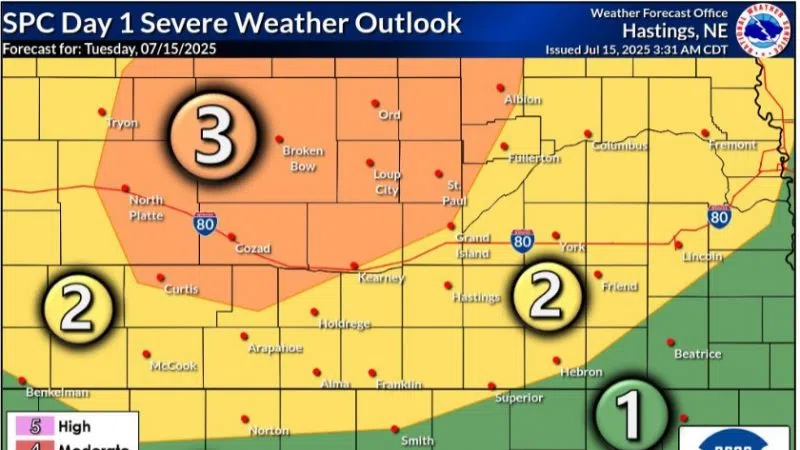

On July 15, Kugler was wounded in action, while Army documents don’t specify exactly how he was wounded, it was serious enough for him to earn the Purple Heart. He was evacuated from the front lines and was seen by the 3rd Battalion Aid Station.

Kulger was one of the 636 men of the 43rd Division which were wounded during the drive to Munda, a further 90 were killed and over 1,000 were evacuated due to illness.

The drive to Munda Point has been criticized by historians for the missteps taken by the American commanders. Historian Samuel Morison said the choice of Zanana as a landing site was a mistake and sending Kugler’s 172nd regiment south, exposing the 169th, was a poor choice.

As a result of the fighting, the Americans made limited tactical gains toward the airfield and as a result soldiers experienced an unusually high number of severe cases of combat stress. The Japanese would counterattack on July 17 and bring the Allied drive to a halt temporarily.

Munda Point and the airfield would later be captured in fighting which raged from July 22 to Aug. 5. The airfield would prove to be important in the later Bougainville campaign as over 100 Allied aircraft were stationed at Munda.

Kugler would recover from his wounds and be awarded the Combat Infantry Badge for his service in the campaign. He would go on to fight in 1944 in the Southern Philippines where he would be wounded again and receive his second Purple Heart. Other citations he earned were a Bronze Star and Philippine Liberation ribbon.

Kugler would finish the war as a private first class with the 124th infantry regiment and be honorably discharged on July 12, 1945. He would return to the Lexington area where he would remain a life-long resident, rarely speaking of his war experiences.

He died at the age of 61 and was buried in Lexington’s Greenwood Cemetery, his gravestone marking him as a World War II veteran.

Tom Kugler’s grave located in Lexington’s Greenwood Cemetery, (Brian Neben, Courtesy)